Your Trauma Is Valid Even If

Gaslighting Statements

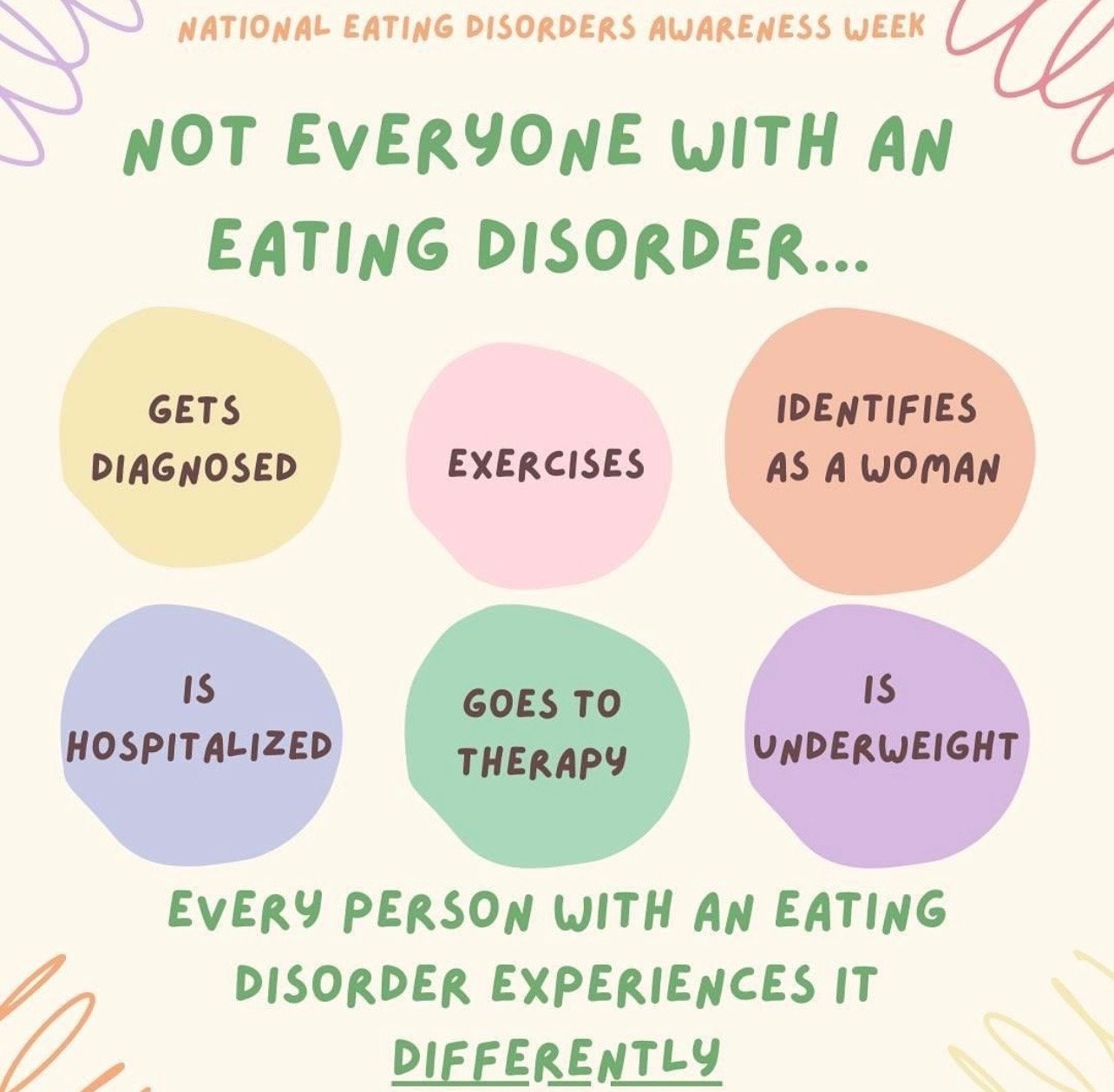

Not Everyone With An Eating Disorder...

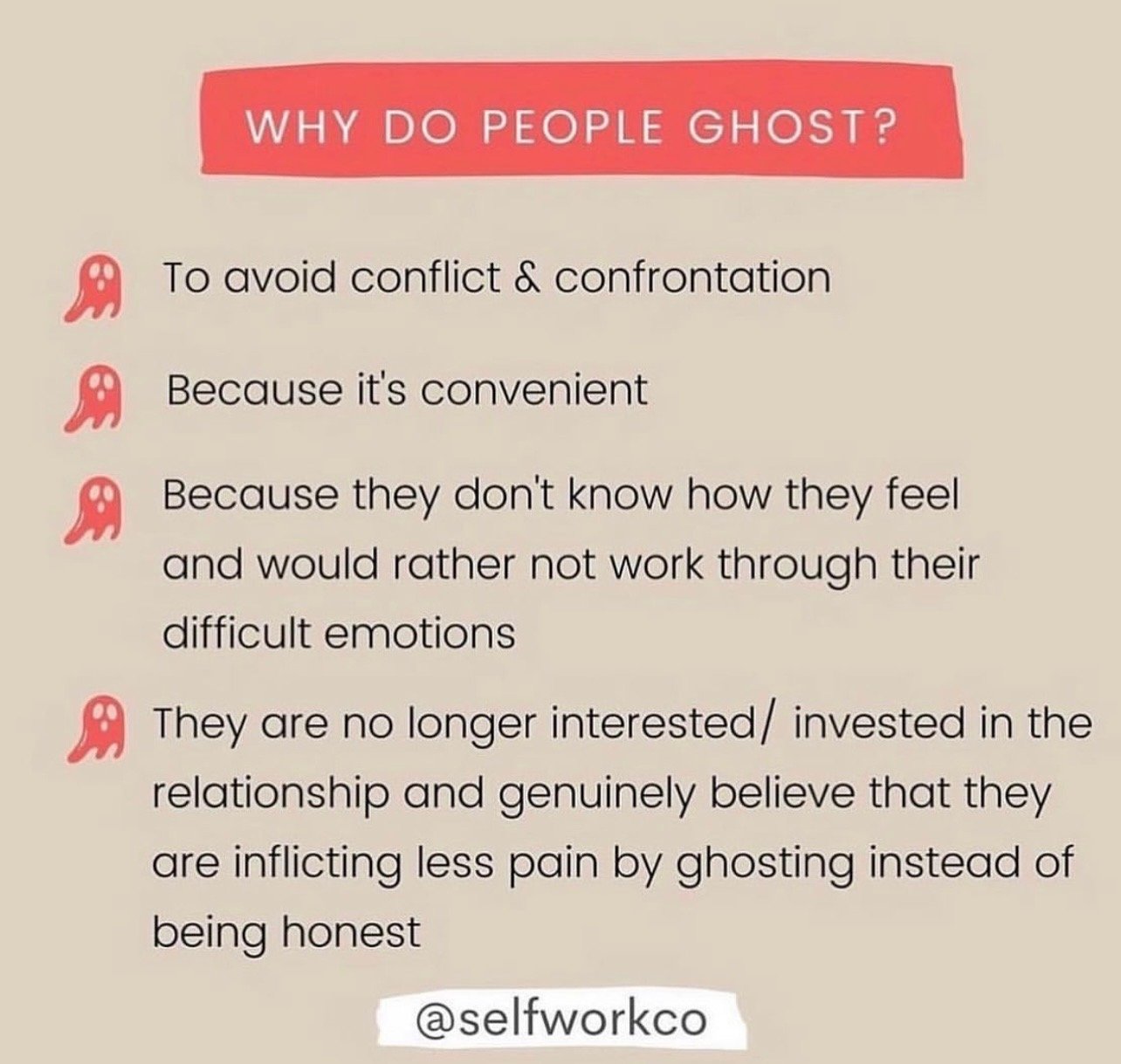

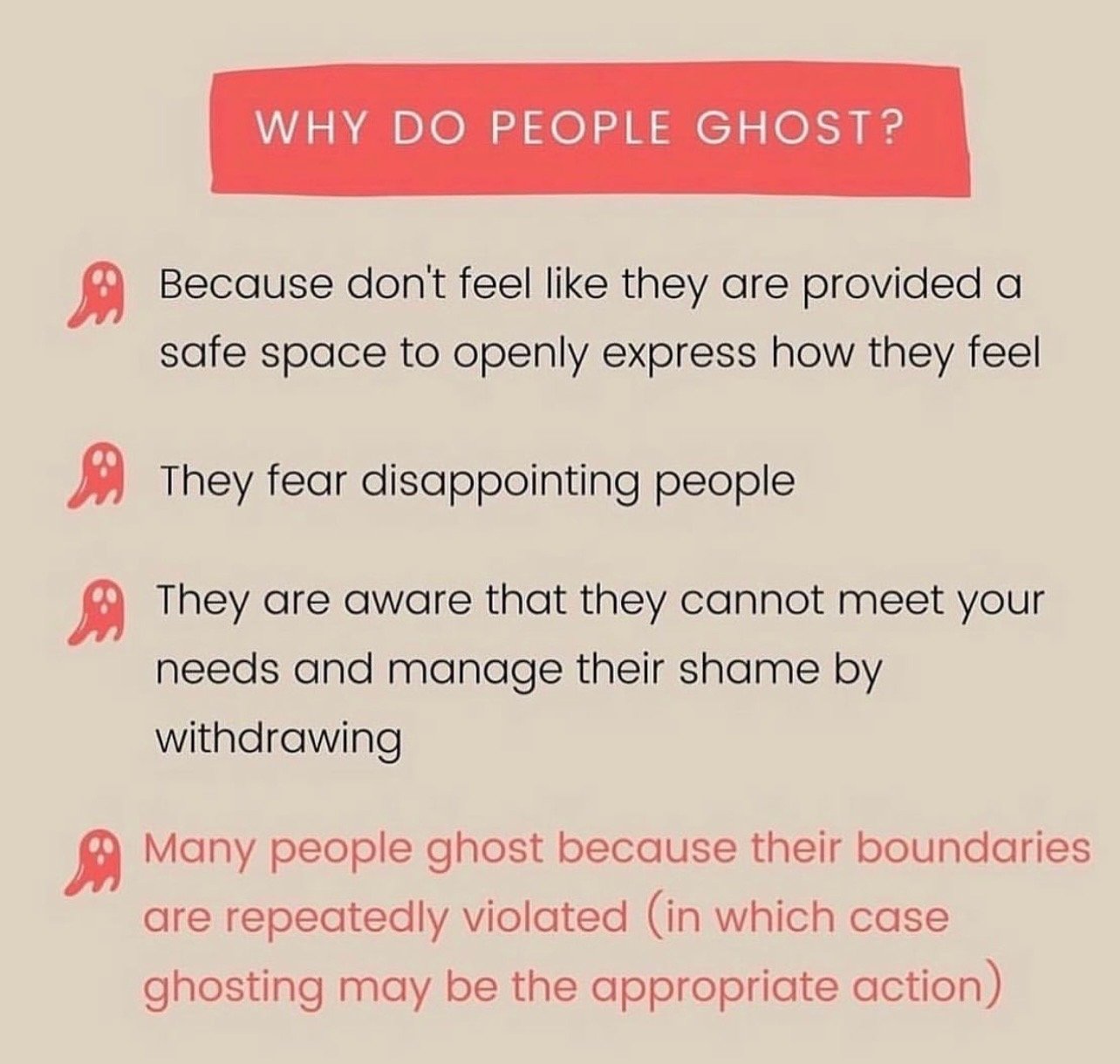

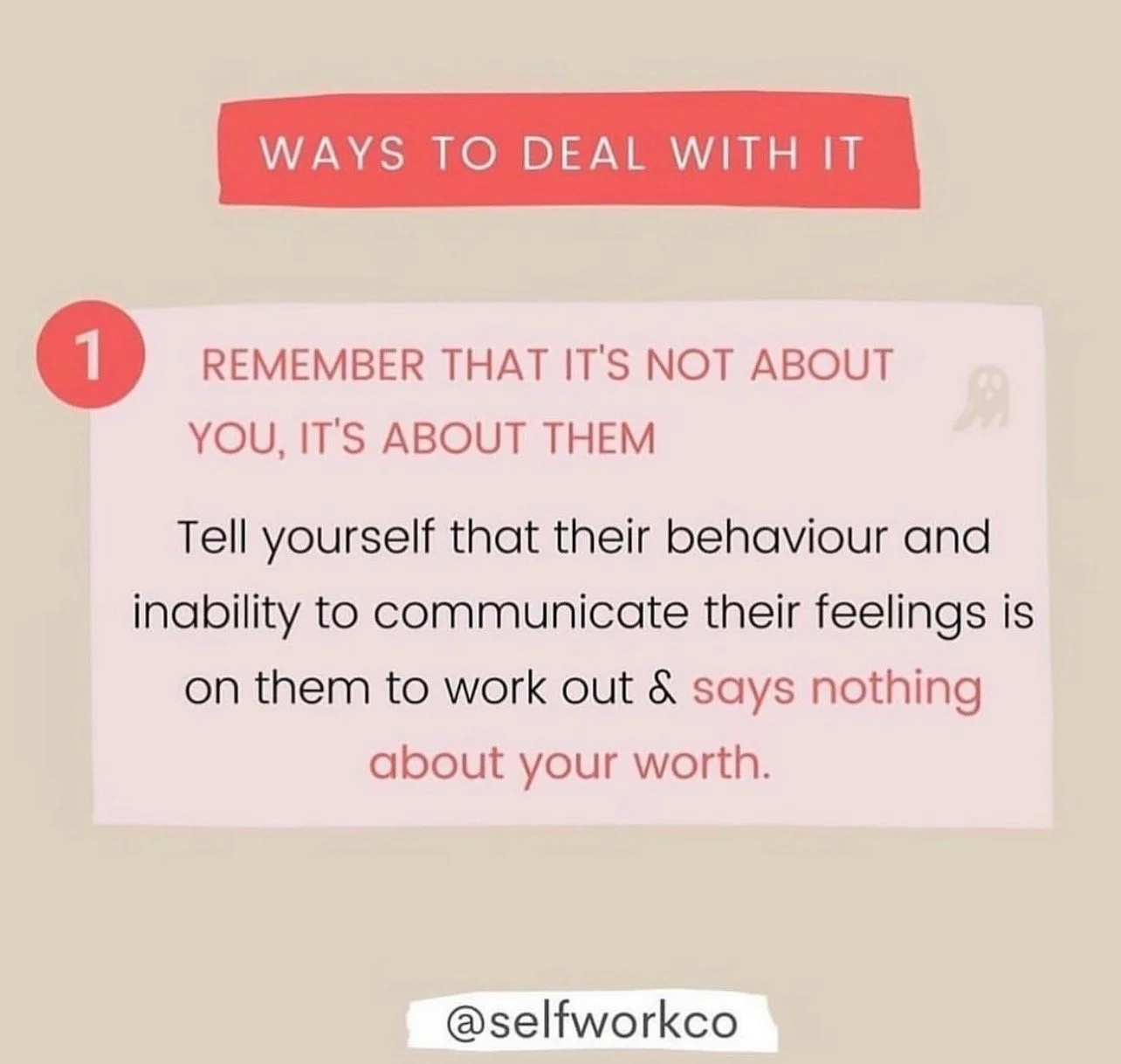

Ghosting and Ways To Deal With It

How to Practice Self Compassion

How to Practice Self-Compassion

Sarah Winnig, MA

Self-compassion means showing kindness to yourself. It means accepting yourself for who you are, imperfections and all.

Self-compassion does not mean giving up on growth and self-improvement. Instead, it's about understanding that you are a work in progress, with strengths and weaknesses, and knowing that is okay.

You probably show compassion to others without giving it a second thought.

Imagine your best friend just went through a break-up. They tell you the story, and you listen from start to finish. Your friend isn't perfect, but they deserve to be happy. You reassure them that they’ll get through this, they’re a catch, and they'll be okay.

You don’t judge your friend. You don’t tell them they are not worthy, or that they need to change. You show your friend compassion.

For many people, it’s easy to show compassion to others. Family, friends, pets, strangers, and even TV characters are met with kindness and understanding, despite their flaws.

At the same time, many compassionate people are critical and unforgiving of themselves. They hold themselves to a standard they would never demand from others. They struggle to practice self-compassion.

There are no simple tricks for developing self-compassion, but there are several healthy habits that may help.

Have a Fair Attitude Toward Yourself

(rather than a critical or judgmental attitude)

Practicing self-compassion means treating yourself warmly, gently, and fairly. It’s about having an attitude of acceptance toward yourself—rather than judgment—and treating yourself accordingly.

Imagine receiving some constructive criticism from your boss. Coming from a place of judgment, you only hear the negative, and tell yourself, “I’m an idiot. I can’t do anything right.” Coming from a place of fairness and acceptance, you hear the whole message, and tell yourself, “There are definitely things I can work on, but I’m doing a good job overall.”

Self-compassionate people believe that they are good, well-meaning, and competent. When they make a mistake at work, it’s just that—a single mistake. People who are not self-compassionate often assume the worst about themselves. A mistake at work is viewed as something much bigger, such as a personal failing.

When you’re critical and judgmental of yourself, you’re more likely to experience unhappiness, insecurity, and anxiety. When you treat yourself fairly, you are better able to manage these uncomfortable feelings.

Having a fair attitude toward yourself looks like...

“I may have said the wrong thing. I’ll get it right next time.” vs. “I may have said the wrong thing. I’m the worst!”

“I made a mistake. I’m only human.” vs. “I made a mistake. I always mess up.”

Accept Yourself for Who You Are

(rather than trying to be someone else)

Many of us have ideas about who we "should” be. A man might believe he has to be strong, brave, and outgoing. A mother might believe she always has to put her needs last. For many, not matching these ideals feels like a flaw.

In reality, humans aren’t so simple. While some men are strong, brave, and outgoing, others are shy, emotional, and cautious. While some mothers do put their needs last, others value their career as much as their family life. It sounds like a cliché, but everyone is different... and that’s okay.

People who are self-compassionate accept themselves for who they are, rather than who they “should” be. Not only that, but they often take pride in their unique characteristics. For example, a self-compassionate man who is emotional might view himself as being deeply connected to others, rather than having a weakness.

Self-acceptance does not mean loving every little thing about yourself, or believing you are perfect. It means accepting yourself for who you are, rather than who you are not.

Note: Self-acceptance isn’t just about gender roles. It includes personality, interests, sexuality, religion, abilities, appearance, and anything else that makes you who you are.

Accepting yourself looks like...

A mother who values her career highly could view herself as highly motivated, a role model, and recognize how she provides for her family.

A person who wishes they had straight hair could see examples of beautiful curly hair like their own, and learn to appreciate what they have. They might still wish to have straight hair, but they learn to like their curly hair, too.

A person who is not athletic but loves sports could find themself fitting into coaching or support roles.

Take Care of Yourself

(rather than denying your needs or overindulging)

Even when life gets busy, it’s important to look out for your own health and happiness, and take care of your needs. This means eating regular meals, getting enough sleep, taking time for fun and relaxation, or whatever it is you need.

Taking care of yourself is not the same as spoiling or overindulging. For example, taking a break to eat a healthy meal is not the same as eating whatever you want, whenever you want.

This might be easier to understand when you think about caring for someone else. If you’re caring for a young child, you don’t ignore them when they're hungry. But that doesn’t mean you give them an ice cream sundae for breakfast. You think about what’s best for them, and take care of their needs accordingly.

Caring for yourself requires a balance between immediate needs and long-term goals. For example, if you’ve been studying for hours, it’s reasonable to take a break. However, if you want to pass an exam, you do need to study at some point.

Sometimes long-term goals will require discomfort, such as studying or exercising when you’d rather relax on the couch. There’s no simple answer for how much discomfort or sacrifice a person should make—it depends on the individual and their goals. But it’s important to have an awareness of your own needs, and a balance that works for you.

Self-care habits might include...

Taking a day off work to relax.

Eating a healthy meal when you’re hungry.

Exercising regularly, but taking rest days as needed.

Rewarding yourself with a treat when you meet a goal.

Accept That Struggle is Normal

(rather than feeling uniquely bad)

You have a front-row seat to your own imperfections and mistakes. While others can hide their insecurities, you can’t hide from yourself. When you feel bad about yourself, or when you make a mistake, it might seem like you’re the only one.

Remember that no one is perfect. Being imperfect is part of being human. Everyone has bad days, loses their temper, and makes mistakes. Sometimes, those mistakes are really big.

Whatever your struggle, try to put it in perspective. Know that it’s normal to have flaws and make mistakes, even if you don’t always see them in others.

Recognizing that your struggles are normal gives you permission to feel self-compassion, despite any shortcomings.

The language of accepting struggle...

“No one is perfect. Everyone makes mistakes.”

“Everyone feels sad sometimes. This is normal.”

“I’m not the first person to make this mistake.”

Practice Mindful Awareness

(rather than getting caught up in thoughts and feelings)

Mindfulness means taking a step back from your thoughts and emotions, and seeing them objectively. This is how you see others’ thoughts and feelings: logically and from a distance. Creating distance from your own thoughts and feelings lessens the power they have over you.

In addition to creating distance, mindfulness will help you become accepting of your feelings. It’s common to think “I shouldn’t be sad” or “I shouldn’t be angry.” Mindfulness lets you acknowledge your feelings, without the need to change them. “I shouldn’t be angry” becomes “I am angry, and that is okay.”

Mindfulness builds self-compassion by creating perspective and acceptance of your thoughts and feelings. This lets you take control of your life, rather than being at the whim of your emotions. Additionally, mindfulness will help you practice other self-compassion habits, like recognizing when you are being judgmental toward yourself, ignoring your needs, or failing to see your struggles as normal.

Learning to view your experiences mindfully makes everything else easier. When you take a step back, you can see things more clearly.

The language of mindful awareness...

“I am treating myself judgmentally. I know I'm not being fair to myself.”

“I feel angry at myself, but that does not mean I am a bad person.”

“I am caught up in this problem, but it is not the end of the world.”

In Summary

Unsurprisingly, practicing self-compassion is easier said than done. Many people focus on their flaws and feel that they are not worthy of kindness. Others set unrealistic goals, demanding nothing less than perfection.

After a lifetime of self-judgment, the habit is difficult to break. It becomes reflexive. But with practice, these reflexes can be unlearned, and replaced with self-compassion.

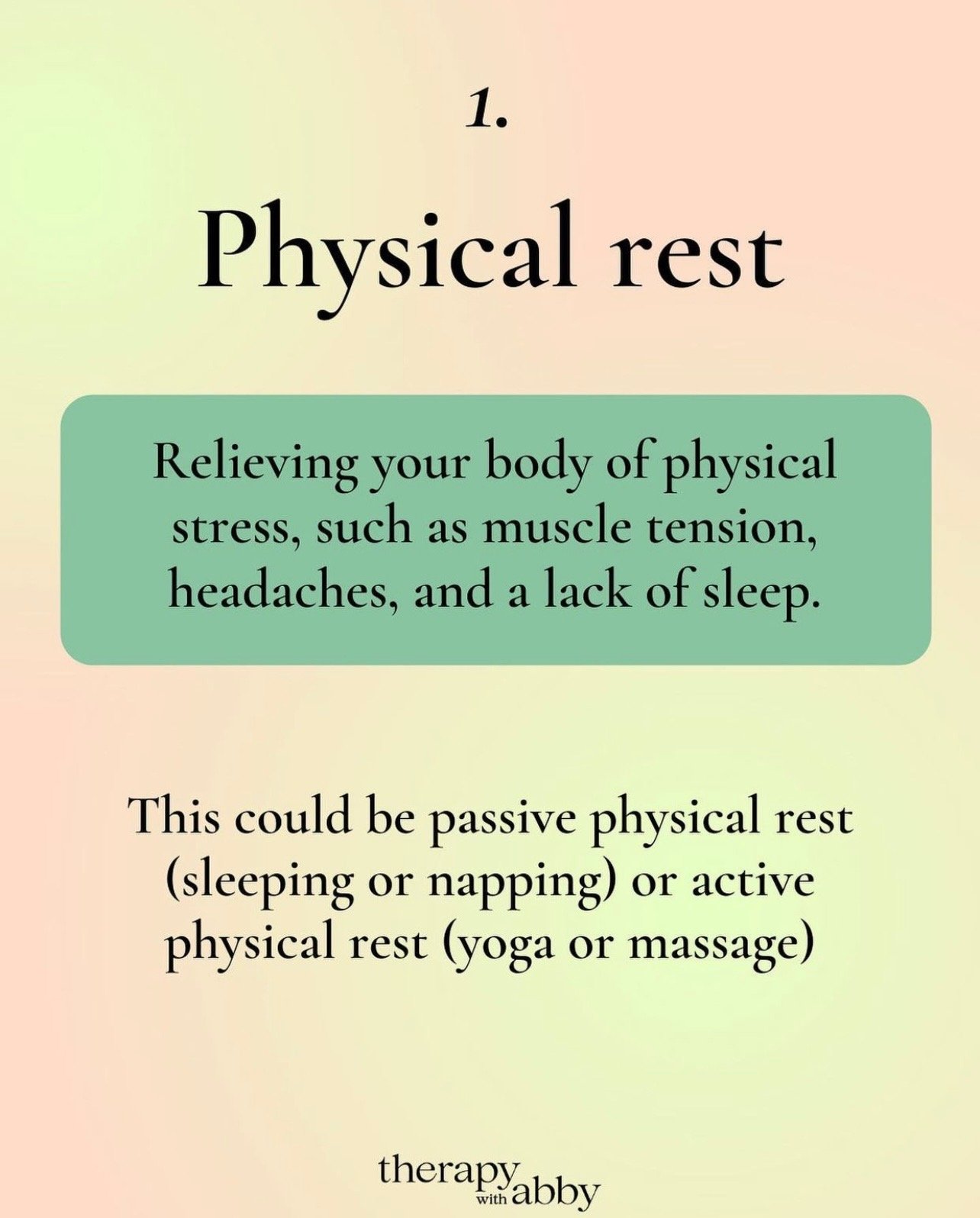

The Seven Types of Rest Everyone Needs

Elements of Glow

I Don't Mean to be Rude When I...

One of the scariest parts of OCD...

From Comfort Zone to Growth...

Affirmations for the Chronic Overthinker

The Highs & The Lows...

Coping with Stress

Coping with stress

By Barry S. Anton, PhD, APA President

December 2015, Vol 46, No. 11

3 min read

"For fast-acting relief, try slowing down."

— Lily Tomlin

I didn't know what to expect when I walked into my 50th high school reunion in October. Mixed feelings of anxiety and joyful anticipation swirled inside me. I felt my heart beating like I was going to the junior prom. I took a few deep breaths to calm myself and ventured in. I worried that I wouldn't recognize anyone without their yearbook pictures on their name tags. Luckily, the festive mood and warm greetings of old friends immediately dissipated my stress.

It was over too fast, but it was a nice interlude in my stress-filled life. As I got into my car late that Saturday night, I thought about the next day's travel to Washington, D.C., for the APA Education Leadership Conference and our upcoming meetings on Capitol Hill to advocate for subsidized student loans. Another stressful week in a long series of stressful weeks.

As psychologists, we know that stress and anxiety are flight-or-fight responses to threats. Feeling emotional or having difficulty sleeping and eating can all be natural reactions to stress, whether it's acute or chronic. Fear and worry can activate the physiological release of hormones that speed up our hearts, increase our breathing rates and enhance our blood flow. Research shows that long-term activation of the body's stress response can impair the immune system and increase the risk of physical and mental health problems.

As APA's "Stress in America" survey shows us each year, many Americans are living with significant stress. Not surprising given the Great Recession, Americans have been particularly stressed about finances in recent years. Work is one of the most commonly reported sources of stress. The survey also revealed that teen stress rivals adult stress, and teens often feel overwhelmed, depressed and sad. The survey noted that too little sleep coupled with too little exercise, and either overeating or eating unhealthy foods, are common among teens. In addition, teens who reported high stress reported being online about 3.2 hours per day compared to two hours a day for those teens who reported lower stress levels.

What can we do to help Americans cope with chronic stress? Here is some of the advice that APA offers on its public website:

Identify what's causing stress and take action.

Build strong, positive relationships: Connect with supportive friends and family members when you're having a difficult time.

Get regular exercise, eat nourishing food and participate in activities you enjoy.

Stay focused on the positive and avoid negative energy.

Avoid drugs and alcohol.

Rest your mind: Sleep, do yoga, meditate and perform relaxation exercises that can help restore energy.

Get help from a psychologist when you're overwhelmed.

I can't help but reflect on the level of stress that APA governance members and staff have experienced in the past few months in the wake of the independent review report. It found that some APA officials worked with military officials to have APA issue insufficiently restrictive ethical guidelines for military psychologists participating in national security interrogations.

Organizational change and transition can be stressful even in the best of times. APA's governance and staff are feeling enormous pressure to fulfill challenging obligations to help the association move forward. My hope is that we find healthy ways to deal with these transitions and not allow the stressors of change to affect our working relationships.