Learning to Listen to Your Body...

You're not uncool. Making friends as an adult is just hard

When you were a kid, it seemed like you could walk up to just about anybody and be best friends the next minute. But somewhere along the long, winding road to adulthood, making new friends became an impossibly hard thing to do.

Well according to psychologist and University of Maryland professor Marisa G. Franco, that’s because as you get older, making friends no longer happens organically.

“Sociologists have kind of identified the ingredients that need to be in place for us to make friends organically, and they are continuous unplanned interaction and shared vulnerability,” says Franco, who is writing a book on making friends as an adult. “But as we become adults, we have less and less environments where those ingredients are at play.”

Tips for forming new friendships:

• Be intentional about making friends

• Set up planned and regular interactions

• Assume that people already like you

• Make the ask and get contact information when you connect with someone

• Don’t be too hard on yourself

• Keep putting yourself out there

If we continue to expect friendships to happen naturally like they did when we were kids, we run the risk of waiting for something that might never come. Being intentional is essential, she says. Research shows those who view friendships as something that happens because of luck are lonelier later on in life, she says, “and those who see it as something that happens based on effort are less lonely years later.”

Juliana Clark, a 25-year-old audio producer living in Los Angeles, says that while she’s been able to make a few friends here and there, she is mostly looking for a community. Spending a few minutes with a new acquaintance doesn’t usually leave her with a feeling that a new friendship is blossoming.

“I'm really more interested in kind of creating a sustainable community that will last,” she says, “especially since at least so many of the friendships that I've made just in my life have kind of had these common experiences anchoring them.”

According to Franco, the key to building a community of friends is setting up planned interactions, like regular group events or rotating potlucks.

“Researchers also find that when we develop groups, our friendships are more sustainable than they are with individuals. Because there's multiple touch points now, right? Someone else in the group could reach out to all of us, and then we all keep in touch,” she notes.

If that sounds terrifying to you, Franco says it’s crucial to assume that people already like you. Assume any meet ups will go well, she says, which in turn will help build up your confidence.

“We all have this tendency to think we're more likely to be rejected than we actually are,” she says.

How age, gender play a role in forming friendships

As we move through life, our struggles change. People in their 30s and their 40s have voiced how having kids or moving to a new city made it tough for them to form connections.

Kate Hickcox, 42, moved to Maine from New York City with her husband in 2018. The mom of two young children says she and her husband still haven't met any new friends in their more rural life. The pandemic worsened the situation since making plans was off the table.

“I'm also a city girl. I often feel like an outsider when trying to engage with those in my new local Maine community who either grew up here and have established connections or those who moved here because of their love of nature and the outdoors,” she says. “I thought I could force friendship to happen by attending events or participating in local sports or activities.”

Franco says people like Hickcox shouldn’t be too hard on themselves because making friends is tough no matter who you are. She recommends working to overcome covert avoidance — when you show up to an event but are mentally checked out.

“You're on your phone, you're waiting for people to come to you, you're not introducing yourself to people,” she says. “It's not just that you have to attend that event, but you have to overcome covert avoidance by engaging with people when you get there.”

It’s essential to take the extra step and ask for contact information.

“That's really, really key to take it from, ‘Hey, I'm putting myself out there’ to ‘We're actually going to form a connection and begin to form a friendship,’ ” Franco adds.

There's also a number of people who find themselves more and more isolated as they get older. David Troxel never got married and never had children. The 64 year old says that he's been socially disconnected for the last 10 years or more.

“I find that typically, people have all or most of the social connections that they can manage,” Troxel says. “I met somebody several years ago that I thought I might get to be friends with and invited them out to have coffee with me. I was told that this person really had all the friends that they need.”

Franco says men often have more trouble making friends than women because of the way society perceives them. Men are also more likely to rely on their romantic partners for a social network.

“There's this phenomenon called homohysteria, which is the fear of being perceived as gay that I think really, really is destructive for men's friendships,” she says.

Eventually, loneliness can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“If you are in a place of loneliness, you are, according to the research, more likely to assume people are going to reject you,” Franco explains. “You're just sort of hyper vigilant for rejection and social threats. You're more likely to think that social interactions will be more negative and less enjoyable.”

That’s why she says it’s of the utmost importance for people like Troxel to keep putting themselves out there.

“You had this one negative experience. It had sucked. Someone said they had too many friends, right?,” she says. “But that certainly doesn't mean that everybody has too many friends, and that certainly doesn't mean that there aren't people out there that are just waiting for you to connect with them,” she says.

The world is likely more open to you than you think it is, Franco adds, and there’s a chance more people out there want to be your friend.

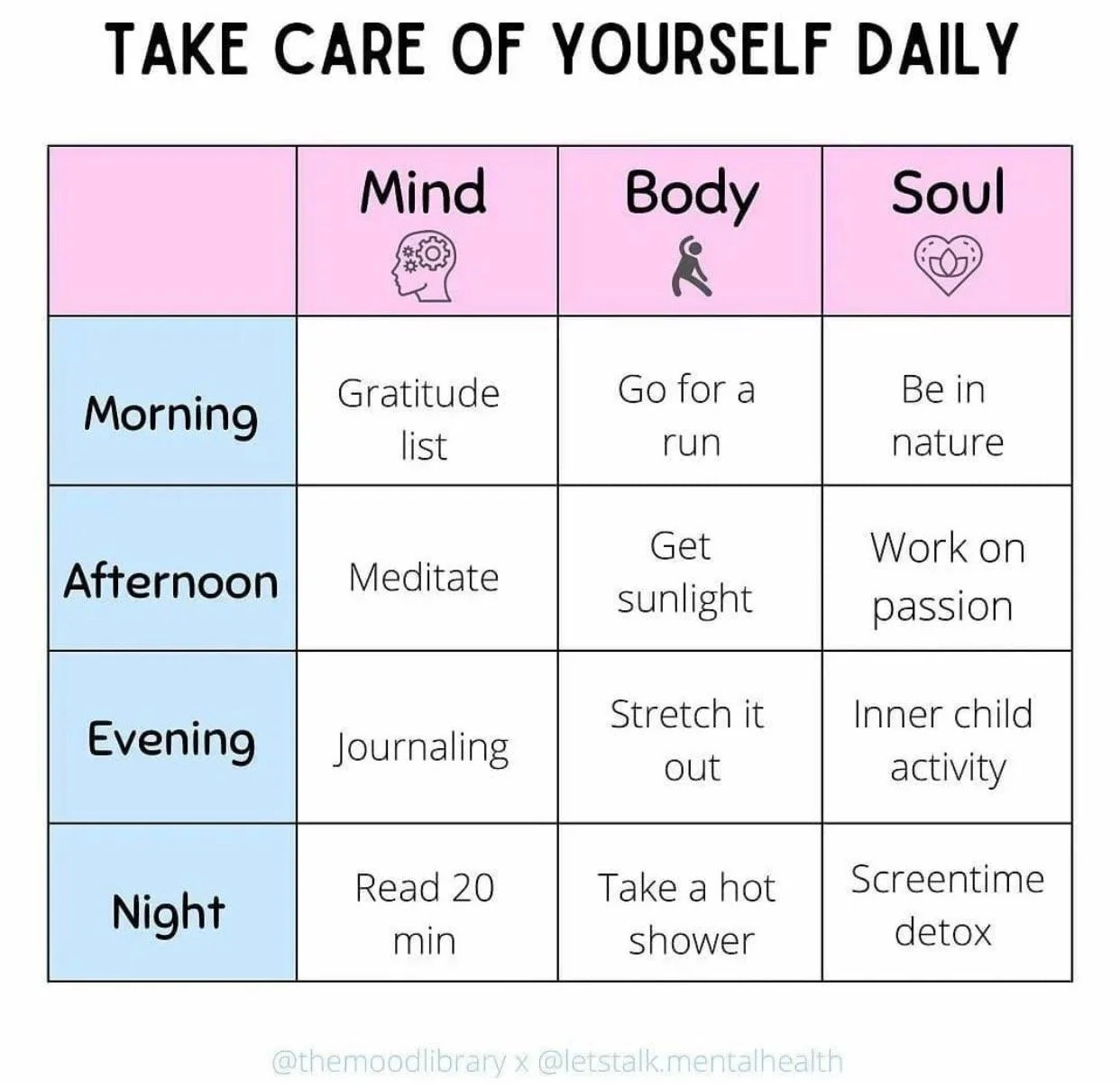

Take Care of Yourself Daily...

Ways To Overcome S.A.D.

Self Discovery Journaling Promps

My Circle of Control

30 Great Accommodations for Children with ADHD

DBT Cheat Sheet

Care & Feeding of Your Grieving Person

You Are Worth More Than Your Late Night Thoughts...

What is Acceptance?

Dating when you have borderline personality disorder: 'I get obsessed really quickly'

Borderline personality disorder affects one in 100 people, according to a mental health charity. It can make romantic relationships intense and difficult. BBC Three speaks to three people about how the condition has affected their relationships

Thea de Gallier November 2021

“When I was diagnosed with BPD, I thought I’d never have healthy relationships.”

That’s how 21-year-old Mae felt when she was told earlier this year that she had borderline personality disorder (BPD) - and it’s a sentiment shared on social media by many others with that diagnosis.

Almost the exact same idea appears as a caption on one of the many videos on the topic on TikTok – content under the hashtag #bpdisorder has amassed over 500,000 views at the time of writing. Much of it is people sharing their own experiences, sometimes with an injection of humour, and a recurring theme that comes up is heartbreak and toxic relationships.

BPD is becoming increasingly visible on social media, and Dr Liana Romaniuk, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, thinks this is partly down to young people having a different approach to it than previous generations.

“I’ve had quite a few young people I work with ask me, ‘could I have BPD?’ I think there’s a growing awareness,” says Dr Romaniuk.

'There were horrible notions people with BPD are manipulative'

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a mental health issue that causes emotional instability and can affect how people manage their moods and interact with other people. It’s thought around one in 100 people have it.

Many people with BPD have experienced trauma or neglect in childhood, which can make relationships difficult as an adult. Dr Romaniuk points out that “trauma” doesn’t have to mean something horrific or abusive – things like parents splitting up, being emotionally distant, or losing a parent at a young age could also have an effect.

Some people with BPD want to frequently call and text who they're dating

Unfortunately, there can be a stigma attached to having a BPD diagnosis. Dr Romaniuk explains: “Professionally, there were a lot of horrible old-school notions that BPD was untreatable or people were being manipulative. Thankfully, that’s not the view held by anyone I work with at the moment.”

There is also an “ongoing debate” in professional circles, says Dr Romaniuk, as to whether BPD is in fact a personality disorder, or a reaction to past trauma.

“I’ve got huge difficulty with the phrase ‘personality disorder’, it feels like you’re stabbing someone in the heart when you say that,” she says. “It sounds like you’re saying there’s something fundamentally wrong with [the person], and that’s not the case. I think about it more in terms of, they’re survivors, they’re adapters.”

Getting 'obsessive' in relationships

Mae started researching BPD because she noticed herself becoming “obsessive” and anxious in relationships.

“I noticed my symptoms were a lot stronger and more dysfunctional when I was in a relationship,” she says, who was diagnosed in March 2021.

“I get obsessive quite quickly. I’ll constantly want to call or text, and I’ll isolate from other friends – I drop hobbies and dedicate all my time to that person.”

Things that seem like a non-event to someone without BPD can be catastrophic.

“One time, I was at my friend’s apartment when I got a text from the boyfriend and the tone really spooked me – I literally picked up all my stuff and said, ‘I’ve got to go’, and ran to his apartment 15 minutes away.

BPD can put a strain on relationships

“I was having a full-on panic attack. It turned out it was fine, so I went back to my friend’s. It must have been really bizarre to her, but I wouldn’t have been able to sit chatting because that panic would’ve continued to mount.”

The fear of abandonment can also manifest as hostility. “In the last few weeks of my last relationship, I was breaking up with them, saying I was going to leave a few times, and being really spiteful,” Mae says.

“Then when they finally broke up with me, I was absolutely crushed, calling them crying, begging to get back together. That relationship ending was directly related to my BPD.”

Since her diagnosis, Mae has started a treatment called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which is a type of talking therapy for people who struggle to regulate their emotions. She has also started taking antidepressants.

“I’m feeling a lot more positive,” she says. “When I was first diagnosed it felt like a death sentence, and I was going to be like that for the rest of my life, but the DBT is showing me a way out.”

It’s important to note that not everyone diagnosed with BPD will behave the same way, as Dr Romaniuk points out: “You can’t make an assessment on a whole group of people based on three letters.”

BPD symptoms or abusive behaviour?

The partners of people with BPD can sometimes find it difficult, too – although many with the condition can build healthy relationships, Ellen’s* ex partner, she says, struggled.

The 32-year-old dated a man with diagnosed BPD last year. “I don’t know how things might have been different if he didn’t have BPD,” she says. “I think I excused a lot of abusive behaviour, because I thought maybe it was part of the condition.”

She explains that he would “make me feel guilty” about leaving him alone, to the point she started coming home early from work. “If we had any kind of disagreement, he’d give me the silent treatment,” she continues. “I made a lot of allowances thinking it was the BPD. He started to leave me every three days – he’d leave in the middle of the night, then would come back and tell me I was the love of his life.”

She says some of his behaviour was abusive. But is this a fair label to put on people with the condition?

'Honest conversation' is key to a healthy relationship, says expert

“That’s a really important question that touches on the core of who we are as human beings,” says Dr Romaniuk. “Having BPD, you are still your own self. It might predispose you to responding in certain ways, but I think there’s still a level of responsibility for what you do in a given moment. A lot of the time, the behaviour is not manipulative, but sometimes, it might be.”

More often than not, though, the behaviour comes from fear of abandonment. “From what other people with BPD have told me, there's a tendency to push before you’re pushed,” Dr Romaniuk says. “You might create reasons to end a relationship, or create tests to make sure your partner is really with you. This is subconscious – it’s not overt manipulation. From your brain’s survival point of view, it’s always better to be on your guard and expect the worst.”

She encourages “honest conversation” between partners if one person has BPD, but also for the person without the condition to “have concern for their wellbeing, too.”

She also stresses that every person with BPD is different, and the label doesn’t predispose anyone to a specific set of behaviours: “Some of the loveliest, most dynamic, interesting people I know have BPD.”

*Some names have been changed