12 most beautiful questions ever asked

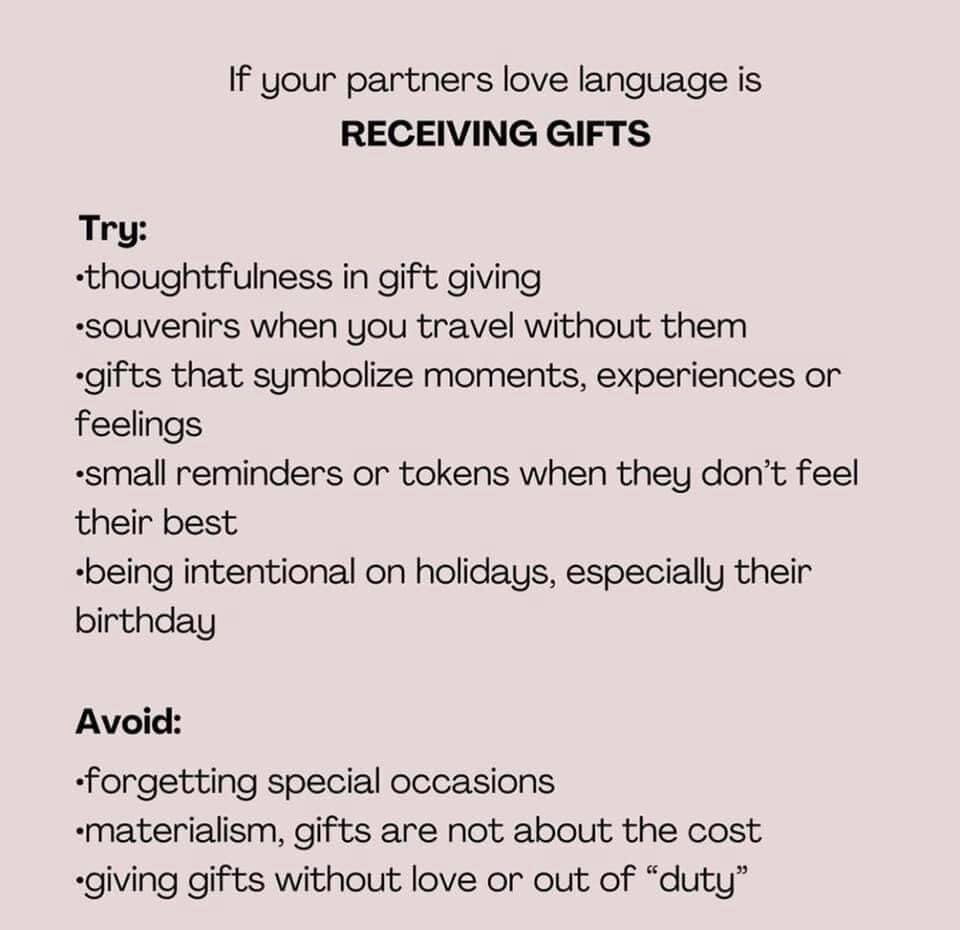

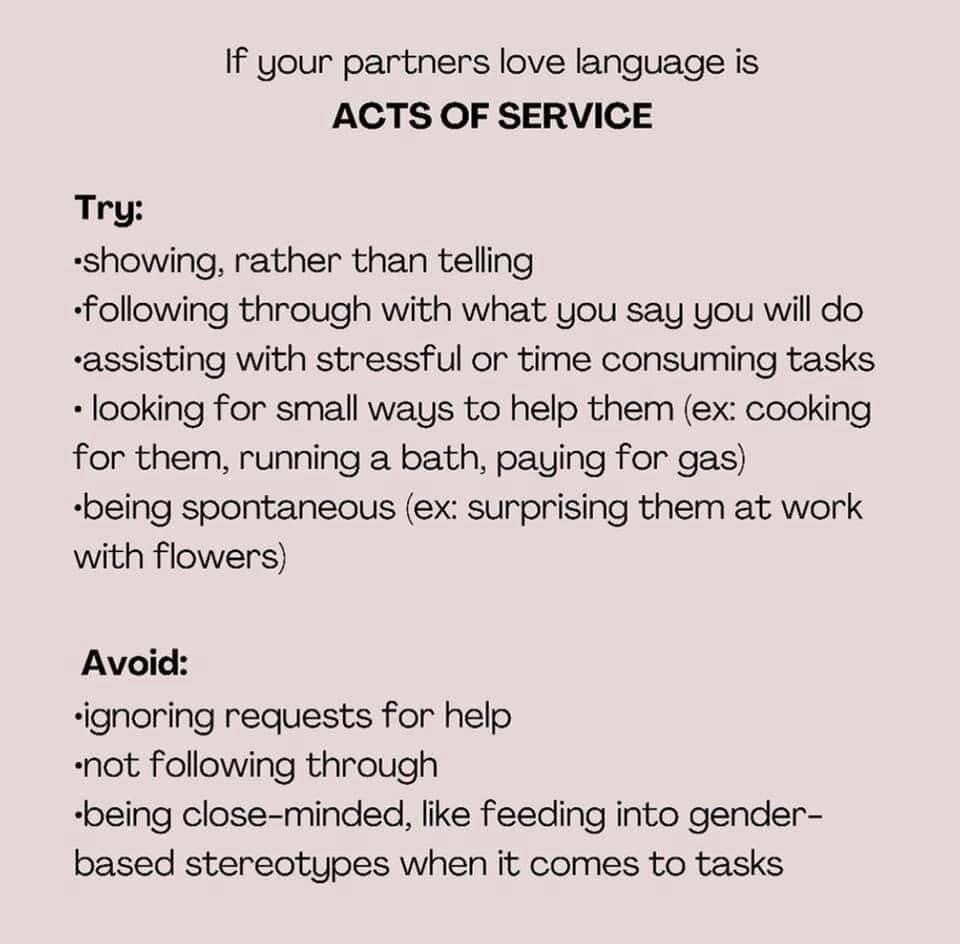

Tips to Support Your Partner’s Love Language

Thoughts Of Suicide, Other Mental Health Struggles Still High For LGBTQ Youth

Forty percent of young LGBTQ people have considered suicide in the last year; that rises to more than half for trans and non-binary youth.

That's according to the second annual survey on LGBTQ youth mental health by The Trevor Project. The non-profit organization provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to LGBTQ people under the age of 25.

Two years of data isn't enough to show trends, says clinical psychologist Amy Green, who is also the director of research at The Trevor Project. But what they do show, she says, is that "the numbers are high and staying high, in terms of mental health."

"LGBTQ youth already deal with housing instability, food insecurity and trouble accessing health care," she says. "All of that is exacerbated by a pandemic."

More than 40,000 people, age 13 to 24, responded to the survey, which The Trevor Project says is the largest of its kind. It was conducted between December 2019 and March 2020 — as COVID-19 restrictions began to take hold.

Many students and recent graduates had to decide whether to move back in with their families.

For 24-year old Mia Soza, going home was not an option. Soza moved to Nashville earlier this year. She quit her job at a flower shop when the stress of dealing with racist customers got to be too much. Living in a new city was already hard; the pandemic and unemployment only added to the pressure.

Soza says she hasn't met anyone in Nashville who she can relate to about being "queer and brown."

"I am very unstable right now," Soza says. "I am lucky to be living with friends. But I don't receive any support from my parents, largely because they don't really accept me because of my identity. They are Trump supporters and also Latino."

That sentiment is reflected in the survey results as well: 86% of LGBTQ youth said recent politics have negatively impacted their well-being, up from 76% last year.

While it's "liberating to feel the comfort of knowing" who she is, Soza says she feels like a lot of things haven't changed since her middle and high school days. "I feel very much like that kid, there is no one to talk to."

The survey found that 46% of LGBTQ youth said they wanted counseling from a mental health professional but were unable to receive it in the past 12 months. The top barriers were affordability and parental permission.

Not being accepted by family members also can have an impact on mental health. Six out of 10 LGBTQ youth said that someone — a relative, religious leader — tried to convince them to change their sexuality or gender.

But even those who live in an accepting family face challenges.

Madison Hall was laid off from her job in February and had plans to go home to visit her parents in March. But her two-week stay turned into multiple months due to the pandemic. The 23-year-old says it's the longest she's spent with her parents since coming out to them as trans.

Hall says her parents were always affirming. Yet, she says, she still wasn't comfortable being her full self in front of them when she moved back in. She characterizes the process as a "trust exercise," requiring much back and forth.

"Yes, I'm her daughter and child, but those 'Let me dress you up' kind of bonds that stem from childhood aren't necessarily there," Hall says of her mom. "She wants to be let in, and I have to let my parents in. I think that's probably a good metaphor to transitioning in general for me. It's letting them know a little, little by little, until we're on the same page."

The time together is improving Hall's relationship with her parents, and she says it's had a positive effect on her mental health.

Amit Paley, CEO of The Trevor Project, says that one affirming adult can have a big impact on LGBTQ youth.

"We saw that LGBTQ young people who have an accepting adult in their lives were 40% less likely to attempt suicide, which is is a huge impact from a public health perspective," he said during an interview with NPR.

Rhys Hilicki, 17, also has supportive parents. When he came out to them as trans two years ago, Hilicki says they began calling him by his correct name and pronouns almost immediately.

"They remind me to take my medicine and my testosterone shots, they've supported me through my transition and helped me financially with it," he says. "And they've really helped me come out of my shell."

Hilicki says knowing his parents see him fully helps with his depression and anxiety.

Feelings like these are common among LGBTQ youth: 68% percent said they'd experienced generalized anxiety disorder in the past two weeks at the time of the survey, including more than three in four transgender and non-binary youth.

Paley says he hopes the survey results help inform efforts to improve mental health outcomes for the community.

"The reason they face these elevated risks of suicide is not because there is something inherently wrong with LGBTQ people," he says. "The reason that they are facing these negative outcomes is because of the discrimination and bias that exists in society today."

The survey found one in three LGBTQ youth reported that they had been physically threatened or harmed in their lifetime due to their LGBTQ identity. Paley says support from parents and guardians can save lives.

"We hope that people will see those stories of parents who are understanding that when someone comes out it doesn't change who they are," he says. "It's just a part of their identity and it allows them to hopefully be their fuller selves."

Anxiety is more than nervousness

How to speak your partner’s love language

Things you’re allowed to say to your therapist

How Grounding Helps Anxiety

Sometimes, the truth can hurt. It’s still important.

What happens in therapy?

Everyone’s anxiety does not looks the same

Which is it?

Things To Remember

Welcome to the team, Anthony!

Anthony Taylor, LPCA

Anthony Taylor is a Licensed Professional Counselor Associate who earned a Masters Degree in Clinical Psychology from Loyola University Maryland. He utilizes a person-centered, solutions-focused therapeutic approach emphasizing the present and future. His goal is to help individuals achieve meaningful outcomes in their life. Be it learning to navigate difficult social situations or finally ‘doing something about it’ he is there to provide an open and honest environment to facilitate personal understanding and growth.

Anthony is accepting new telehealth clients and provides services on a sliding fee scale.

Feeling Upset? Try This Special Writing Technique

After his father was rushed to the hospital with gastrointestinal bleeding, Yanatha Desouvre began to panic. So he did the one thing he knew would calm himself: He wrote.

“I’m so scared,” Mr. Desouvre started. “I don’t know what I’ll do if I lose my dad.”

In the next few weeks, Mr. Desouvre filled several notebooks, writing about his worry as well as his happy memories—the jokes he’d shared with his dad, the basketball games they’d watched, the time they put up hurricane shutters together, then cooled down with ice cream. Sometimes he cried as he wrote. Often he laughed.

“Writing allowed me to face my fear,” says Mr. Desouvre, a 42 year old who teaches marketing and business at a college in Miami. “My pen was a portal to process the pain.”

Something troubling you?

You should write about it.

An extensive body of research shows that people who write about a traumatic experience or difficult situation in a manner that psychologists refer to as “expressive writing”—recording their deepest thoughts and feelings—often show improved mental and physical health, says James Pennebaker, a psychology professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Pennebaker pioneered the scientific study of expressive writing as a coping mechanism to deal with trauma back in the 1980s.

Expressive writing is a specific technique, and it’s different from just writing in a journal. People need to reflect honestly and thoughtfully on a particular trauma or challenge, and do it in short sessions—15 to 20 minutes for a minimum of three days is a good place to start.

Dr. Pennebaker says that hundreds of studies over several decades have looked at the potential benefits of expressive writing, including for people with illnesses such as cancer, PTSD, depression, asthma and arthritis, and found that it can strengthen the immune system and may help lower the rate of colds or flu. Research also found the technique can help reduce chronic pain and inflammation. It may help lower symptoms of depression and PTSD. And it can improve mood, sleep and memory.

Now, a new website, part of a research endeavor called the Pandemic Project, gives people an opportunity to try expressive writing about the coronavirus. On the site, which was created by a research team led by Dr. Pennebaker, people are prompted to write about how the coronavirus is affecting them. A text analysis program then provides feedback. (This is not an expressive writing study, but the researchers will be analyzing the samples to look for themes around trauma and the coronavirus.)

Expressive writing works because it allows you to take a painful experience, identify it as a problem and make meaning out of it, experts say. Recognizing that something is bothering you is an important first step. Translating that experience into language forces you to organize your thoughts. And creating a narrative gives you a sense of control.

The mere act of labeling a feeling—of putting words to an emotion—can dampen the neural activity in the threat area of the brain and increase activity in the regulatory area, says Annette Stanton, chair of the department of psychology and professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at UCLA. Dr. Stanton’s research suggests that expressive writing can lead to lower depressive symptoms, greater positive mood and enhanced life appreciation. “Writing can increase someone’s acceptance of their experience, and acceptance is calming,” says Dr. Stanton.

Expressive writing can even help your relationships. A 2006 study in the journal Psychological Science found that when one partner wrote about his or her deepest thoughts and feelings about a romantic relationship, both partners began using more positive words when writing each other instant messages, and the couple stayed together longer. “We think expressive writing helps people work through struggles in a relationship, that leads to positivity, and that positivity elicits more positivity in return,” says Richard Slatcher, distinguished professor in the psychology department at the University of Georgia, who was the lead researcher on the study.

What if you hate to write? Don’t worry. You don’t have to put pen to paper. Researchers say that speaking your thoughts into a recorder works just as well. Try expressive writing for 15 to 20 minutes a day for a minimum of three days. Don’t worry about spelling or grammar or share your writing with anyone. But dig deep into your thoughts and feelings. The goal of the exercise is to find meaning in an event.

Hi, I’m Anxiety!

Change you actions, change your mood

#selftalk

The seeds are already there

What To Say When A Friend Is Struggling

We want to be supportive of our friends, colleagues, partners and family members when they're having a hard time. But what does that actually look like?

"Showing up is the act of bearing witness to people's joy, pain, and true selves," Rachel Wilkerson Miller writes in the first chapter of her new book, The Art of Showing Up: How to Be There for Yourself and Your People. "[It's] validating their experiences; easing their load; and communicating that they are not alone in this life."

Miller walks us through the do's and don'ts of showing up for your people.

Keep your focus on your friend.

When a friend is confiding in you, it's easy to let the focus of your conversation drift away from the friend's experience. While it's tempting to chime in with a similar story in an effort to relate and connect, it's not always welcome. Your friend might feel silenced or feel that you've made their pain about you.

If you do feel that your experience might be helpful to hear, Miller's tip is to let them know that you went through something similar but allow them to decide if they want to hear about it in the moment.

"It's the best of both worlds," she says. "You get to tell them they're not alone, but you're not going to bore them with a story about how your pet died after their sibling died. You can let them decide if these things are related or not."

Ask how you can best help.

You don't need to automatically know what kind of help your friend wants. Just ask! Miller says to try these questions:

What's the best way I can support you right now?

Do you need someone to vent to? Or would you like my advice?

How are you feeling about [whatever tough experience your friend is going through]?

Tell me about your thought process.

A heartfelt "I'm sorry" goes a long way.

People may shy away from saying, "I'm sorry" in response to someone's misfortune because it might not feel like enough of an acknowledgment. But Miller says a genuine "I'm sorry" can go a long way to make your friend feel heard and validated.

"Sometimes there isn't a perfect response that is going to make people feel better," she says. "What you want to do is communicate, 'You're not alone. I'm with you. This sucks. I'm so sorry it's happening to you.' "

Lean away from clichés.

Platitudes like "Everything happens for a reason" aren't helpful when you're trying to comfort a friend. Resorting to clichés can make it feel like you're minimizing the friend's pain.

And stay away from statistics. For example, if a friend found out their spouse is cheating, maybe don't try to make them feel less alone by sharing that 50% of marriages end in divorce.

"Feel with your friend the bigness of what they're going through," Miller says. "Remember that just because it happens to a lot of people doesn't mean it's any less devastating."

Try not to "foist" or "fret."

In There Is No Good Card for This, a book outlining strategies for helping loved ones, the authors Kelsey Crowe and Emily McDowell identify two problematic kinds of helpers: foisters and fretters.

Foisters tend to push their advice — to insist on fixing or overcoming the problem. Fretters are so worried about their friend's challenges that they are preoccupied with whether they are doing enough to help.

Try to keep those behaviors in check, Miller says. "No one should have to manage you when they're going through a tragedy."

Showing up isn't a one-time thing.

Anniversaries of difficult dates can be tough. And grief is so complicated and looks different for each person. Remember that your friend might transition through several stages of sorrow, frustration or anger. Keep in touch with them and see if their needs change. "It means a lot to know that your friend is aware and thinking about you," says Miller.