The seeds are already there

What To Say When A Friend Is Struggling

We want to be supportive of our friends, colleagues, partners and family members when they're having a hard time. But what does that actually look like?

"Showing up is the act of bearing witness to people's joy, pain, and true selves," Rachel Wilkerson Miller writes in the first chapter of her new book, The Art of Showing Up: How to Be There for Yourself and Your People. "[It's] validating their experiences; easing their load; and communicating that they are not alone in this life."

Miller walks us through the do's and don'ts of showing up for your people.

Keep your focus on your friend.

When a friend is confiding in you, it's easy to let the focus of your conversation drift away from the friend's experience. While it's tempting to chime in with a similar story in an effort to relate and connect, it's not always welcome. Your friend might feel silenced or feel that you've made their pain about you.

If you do feel that your experience might be helpful to hear, Miller's tip is to let them know that you went through something similar but allow them to decide if they want to hear about it in the moment.

"It's the best of both worlds," she says. "You get to tell them they're not alone, but you're not going to bore them with a story about how your pet died after their sibling died. You can let them decide if these things are related or not."

Ask how you can best help.

You don't need to automatically know what kind of help your friend wants. Just ask! Miller says to try these questions:

What's the best way I can support you right now?

Do you need someone to vent to? Or would you like my advice?

How are you feeling about [whatever tough experience your friend is going through]?

Tell me about your thought process.

A heartfelt "I'm sorry" goes a long way.

People may shy away from saying, "I'm sorry" in response to someone's misfortune because it might not feel like enough of an acknowledgment. But Miller says a genuine "I'm sorry" can go a long way to make your friend feel heard and validated.

"Sometimes there isn't a perfect response that is going to make people feel better," she says. "What you want to do is communicate, 'You're not alone. I'm with you. This sucks. I'm so sorry it's happening to you.' "

Lean away from clichés.

Platitudes like "Everything happens for a reason" aren't helpful when you're trying to comfort a friend. Resorting to clichés can make it feel like you're minimizing the friend's pain.

And stay away from statistics. For example, if a friend found out their spouse is cheating, maybe don't try to make them feel less alone by sharing that 50% of marriages end in divorce.

"Feel with your friend the bigness of what they're going through," Miller says. "Remember that just because it happens to a lot of people doesn't mean it's any less devastating."

Try not to "foist" or "fret."

In There Is No Good Card for This, a book outlining strategies for helping loved ones, the authors Kelsey Crowe and Emily McDowell identify two problematic kinds of helpers: foisters and fretters.

Foisters tend to push their advice — to insist on fixing or overcoming the problem. Fretters are so worried about their friend's challenges that they are preoccupied with whether they are doing enough to help.

Try to keep those behaviors in check, Miller says. "No one should have to manage you when they're going through a tragedy."

Showing up isn't a one-time thing.

Anniversaries of difficult dates can be tough. And grief is so complicated and looks different for each person. Remember that your friend might transition through several stages of sorrow, frustration or anger. Keep in touch with them and see if their needs change. "It means a lot to know that your friend is aware and thinking about you," says Miller.

Anxious? Meditation Can Help You 'Relax Into The Uncertainty' Of The Pandemic

In 2004, ABC News correspondent Dan Harris was broadcasting live on the air on Good Morning America when he started experiencing a panic attack.

"My lungs seized up, my palms started sweating, my mouth dried up. I just couldn't speak," he says. "I had to quit in the middle of my little newscast. And it was really embarrassing."

Harris credits meditation with helping him work through the anxiety that caused that panic attack. He went on to write a memoir, 10% Happier, about his experiences with meditation, and he talks about the subject on his twice-weekly podcast. He's also been hosting a daily meditation online with different leaders in the community of people who study and teach mindfulness techniques.

Harris says that meditation is more important than ever during the global pandemic: "I don't think we should sugarcoat it: It's scary," he says. "I've taken to saying, if you're not anxious right now, you're not paying attention."

Though he's been trying to help people quiet their anxiety with meditation and mindfulness techniques, he's careful to note that meditation isn't a "silver bullet" cure.

"Meditation doesn't make the uncertainty go away," he says. "It's not like I meditate and I'm walking through this pandemic like a unicorn barfing rainbows all the time."

Rather, Harris says, meditation allows people to "relax into the uncertainty. ... It just means that you're able to see that the fear — like everything in the world — will come and go, and that if you just relax for a second, and breathe into it, it will come and go."

On how a leading meditation teacher recommended the loving-kindness meditation as the best support during this pandemic

I had a very negative reaction to loving-kindness meditation [at first]. First of all, the name itself. I mean, could you come up with anything more treacly? And then it gets worse when you actually hear what the practice entails. So here's how it works: You sit and close your eyes and you envision a series of beings, so people or animals. Classically, you start with yourself and then you move on to a good friend, it can be your pet or kid, some easy person in your life that it's very easy to generate warmth for. Then you move on to a mentor, a benefactor or somebody who's played a positive role in your life. ... And then you move on to a neutral person, somebody you often overlook. And this is a poignant category right now, because the neutral people — the people manning the cash registers at the supermarkets and delivering our food and mail, and the neutral people for many of us that we often overlooked — are saving our lives quite literally now.

Then you move on to a difficult person — not hard to find for many of us. And then finally, all beings. In each case, you summon a mental image or a felt sense of your targeted being, and then you repeat a series of phrases. Usually the phrases are, "May you be happy. May you be safe. May you be healthy. May you live with ease." ...

There's a lot of science that strongly suggests that this practice and its variance can produce really meaningful physiological, psychological and behavioral changes. And if you think about it, this is a radical notion, the idea that warmth, friendliness, kindness, dare I say love — these are not factory settings that are unalterable.

You aren't wired a certain way when it comes to your interpersonal relations and unchangeable. In fact, these are skills that you can develop. And that is such a radical notion, that the mind is trainable. I've been doing this loving-kindness meditation now pretty intensively — including going on long retreats where that's all you do — for several years. And I've found it's made a big difference in terms of my inner weather, and how I relate to my own ugliness, because we all have ugliness.

On the important difference between fear and panic

I'm largely stealing this from a rather brilliant woman I met right at the beginning of the pandemic. The first pandemic-themed episode I did was in mid-March. And one of the guests was a woman named Dr. Luana Marques. She's Brazilian by birth, but now works at Harvard as an anxiety expert. And she told me about something called the — I think this is the right name — Yerkes-Dodson [Law]. You can look this up on Google; it's a bell-shaped curve. And it talks about this sort of utility of anxiety, which is an interesting concept. And it kind of gives us permission to not feel bad about the fact that we're feeling a certain amount of justifiable fear and anxiety.

And so at the beginning of the slope, right until you get to the top of the curve, the anxiety and fear that we may be feeling in the face of this pandemic or anything really, makes sense. It motivates us to act. But then it starts to go downhill. And that's when we tip into not very helpful panic, where we constrict and the physiological response is enfeebling and we're not able to make good decisions. That's when we hoard toilet paper or we're nasty to our neighbors or we spread misinformation on Twitter, whatever it may be. So what we want is to be at the top of the Yerkes-Dodson curve with the appropriate amount of anxiety without tipping in to panic. That is where I feel mindfulness meditation — the kind of meditation with which most people are familiar — that's one of the areas where mindfulness meditation can be really helpful.

On how many people are experiencing vivid dreams during the pandemic

I've been having wild dreams — classic anxiety dreams where I'm trying to get somewhere and I can't get there, or I'm being chased or I'm back in school. This is being reported widely across our culture, across the globe, as I understand it, and I was talking to Dr. Mark Epstein about this. ... I had him on the show originally and I was asking him, why do you think we're having these crazy dreams? And, in typical fashion, he gave the disclaimer that he doesn't really know, but his instinct is that we're "processing." That's what we're doing in these dreams is we're sort of flushing out, purging, processing the — this is his term, not mine — the collective trauma and the collective grief we're all experiencing right now. It can be jarring to have these dreams, but you might look at it as the functioning of a healthy brain and mind.

On how to practice mindfulness meditation

You sit in a quiet enough spot and you then bring your full attention to the feeling of your breath coming in and going out. You don't have to breathe in any special way. This is not actually a breathing exercise. And there's nothing special about the breath per se, we're just picking something south of your neck to pay attention, we're going to get your attention out of the swirling stories in your head and onto the raw data of your physical sensations.

So it can be your breath. For some of us, the breath right now is triggering, given the fact that COVID-19, has pulmonary consequences. So you might want to pick just the feeling of your full body sitting or lying — or maybe your hands touching, or your bottom on your chair, just picking some physical anchor to where you can place your mind and you just kind of commit to it, gently, that I'm going to pay attention to this for one to five to 10 minutes.

That's the second step, and then the third step, the final step really, and this is the most important step — as soon as you try to do this, your mind will go into a mutiny mode. You're going to start thinking about, when can I get a haircut? Where do gerbils run wild? Why did Dances with Wolves beat Goodfellas for Best Picture in 1991? Blah, blah, blah. And the whole game is just to notice when you've become distracted and to start again, and again, and again.

And this distraction, by the way, is not a failure. It is not a malfunction. It is part of the meditation. The key part of meditation is to get distracted, to see the wildness of your own mind over and over and over again, and then to begin again and again and again. ... It is the seeing of the wildness of the cacophony that is really important, because when you see it, it doesn't own you as much.

On why meditation isn't about controlling your mind

It's actually not about trying to tamp down on or control the way the mind works. It's about familiarization. Just getting to know how nutty it is inside your brain, inside your mind, is incredibly important, because when you've tipped over into panic or any other unhelpful, unskillful mind state — like greed or anger or hatred — then you might notice it. And then you have a choice: Am I going to be owned by this panic right now or am I going to be owned by this anger right now? Or am I going to be so controlled by the anger that I'm going to say something that's going to ruin the next 48 hours of my marriage? Or am I going to eat the 75th Oreo?

Having this self-awareness — otherwise known as mindfulness — which is what's developed through the process of seeing your distractions and then beginning again (gently over and over and over again), that is a game-changing skill. Because ... this nonstop conversation ... is a central feature of your life — whether you know it or not, we're all walking around with this inner narrator that if we broadcast loud, you would be locked up. And when you're unaware of this cacophony internally, it's owning you all the time. And what we're doing in meditation is dragging all of this nonsense out of the shadows and into the light.

On why focusing your energy on helping others can quiet the feelings of loneliness and despair during the pandemic

Helping other people puts you back in touch with what is good about you. And it can take you out of the black hole of self-obsession. And those are two really useful benefits of helping other people. It doesn't have to be grandiose. It doesn't have to be giving away all of your money. It can be running errands for your elderly neighbor. It can be checking in on friends. It can be making small donations to charity. It can be volunteering at a safe social distance with local nonprofit groups. There are lots of ways to help out. Adopting a cat, adopting a dog — many, many ways to get you out of the self-obsessed dialogue and put you in touch with your best characteristics, which are helping.

How to reframe negative thoughts

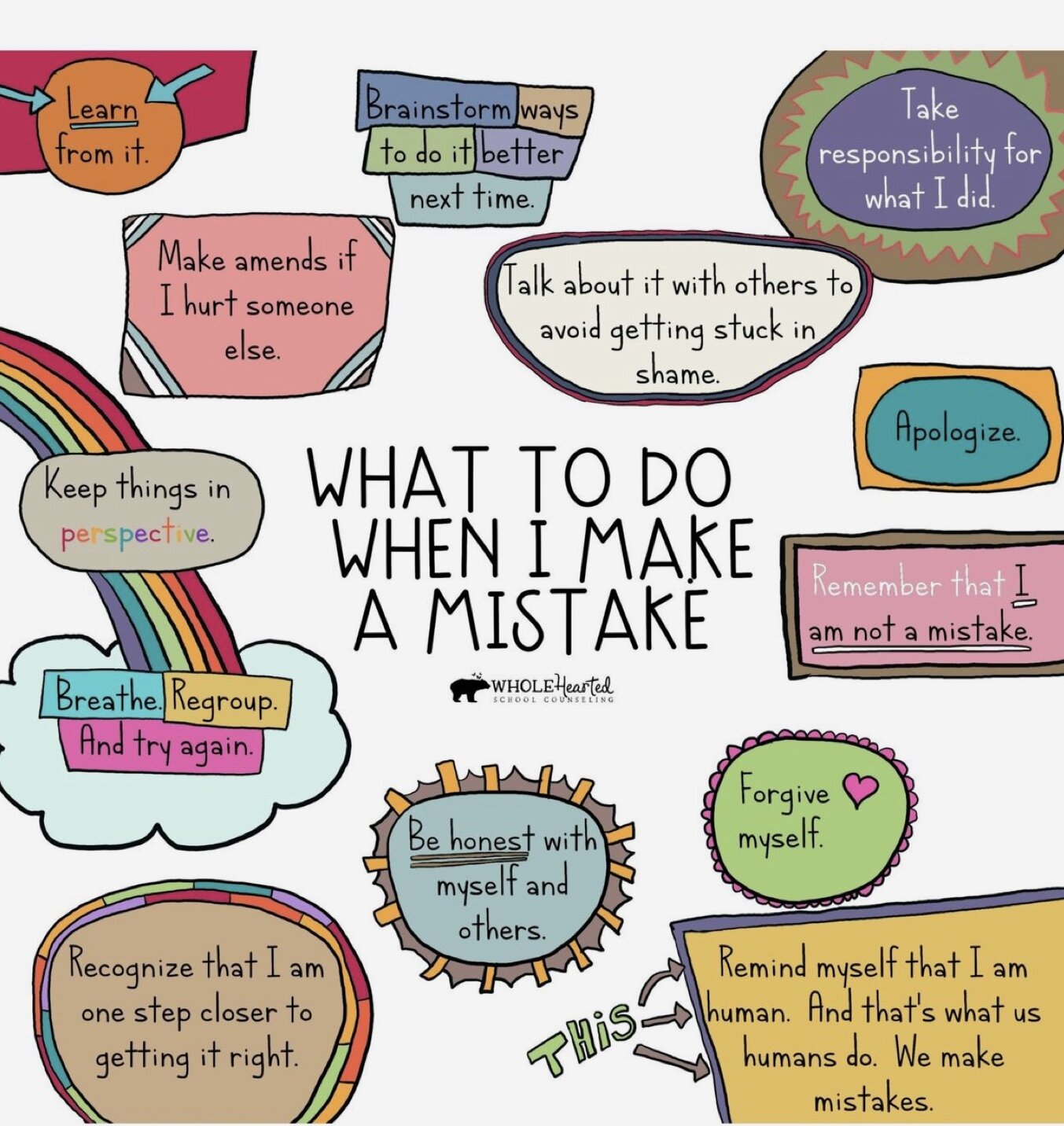

Mistakes happen, so what’s next?

The Science of Happiness

You’re making progress, even if it doesn’t feel like it.

Be yourself. Everyone else is taken.

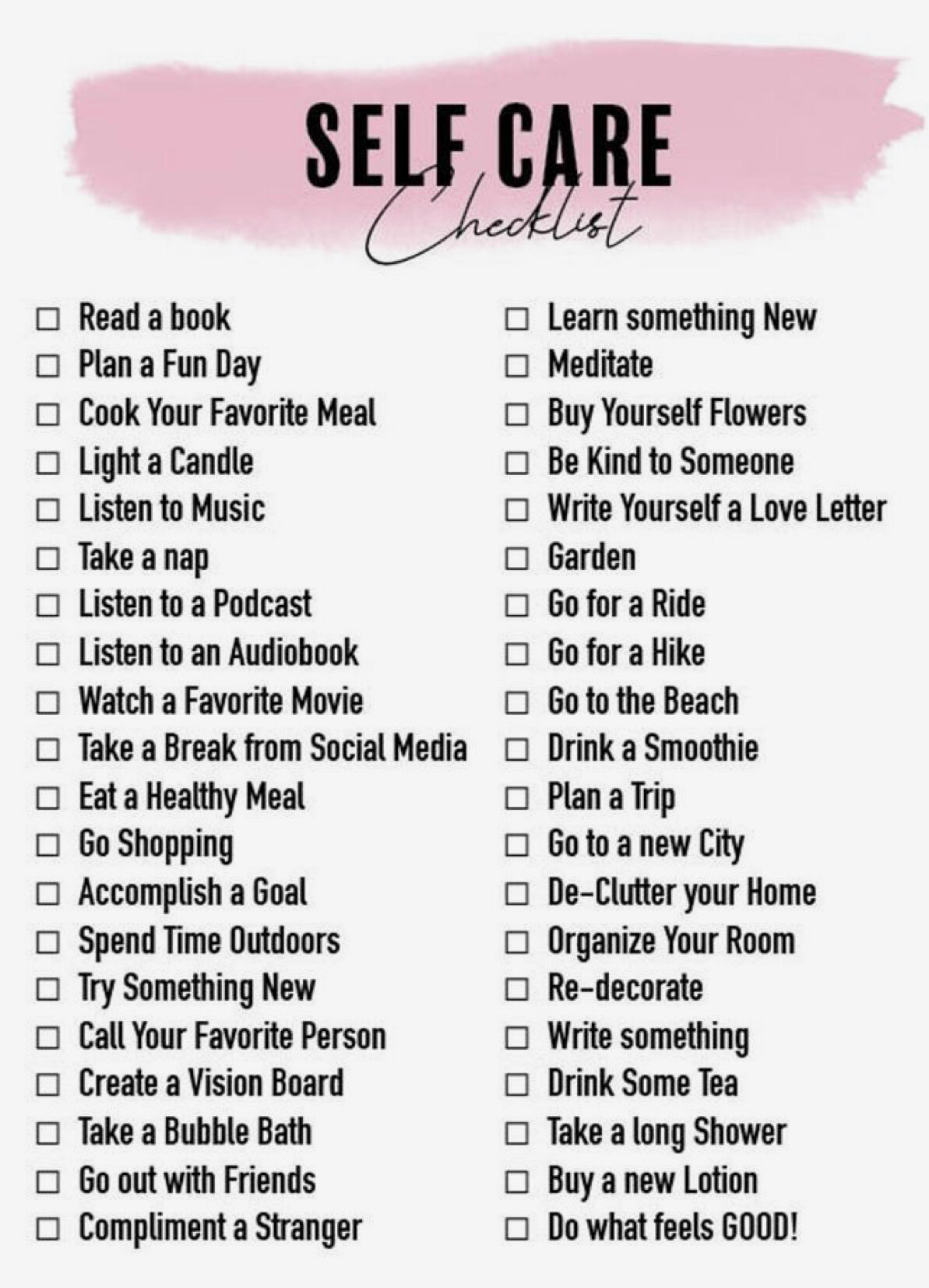

Self Care Checklist

4 ways to take care of your mental health during the coronavirus pandemic

Millions in the U.S. and around the world are under stay-at-home orders as officials hope to slow the spread of the coronavirus. But how do those practices affect individuals’ mental health? What are the unique mental health challenges people are facing during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how do they affect health care workers, those living alone and those returning to work, among others?

Psychiatrist Dr. Jessi Gold of Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis and PBS NewsHour’s Amna Nawaz answered viewer questions on how to take care of our mental health and cope with things like fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic on May 6.

What are some tips on how to deal with anxiety from uncertainty?

A major cause of anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic is the uncertainty about what the near future will hold, which can be exacerbated by the prevalence of misinformation about the virus, Gold said.

Gold said the reason why we feel anxiety hearkens back to primal instincts to be aware of our surroundings, and to always be prepared to run from predators.

“It’s really, really normal,” she said. “Everyone is dealing with anxiety.”

Gold recommended everyone stay informed through their favorite, trustworthy, news sources to help alleviate some uncertainty, but to also limit that time in an effort to not get overwhelmed.

“I think you have to stay informed to some degree,” she said.

Anxiety can also come from growing daily to-do lists. Even the midst of all the demands, Gold recommends people always be kind to themselves.

“You’re going to be less productive right now,” she said, urging people to be patient with themselves.

She suggested breaking down big tasks into smaller, more manageable pieces to make them feel less daunting.

Beyond that, Gold said to explore relaxation methods such as meditation, but also said that method does not work for everyone.

“Don’t beat yourself up if it isn’t for you,” she said.

She also recommended activities like exercising and listing some of your favorite things as a way to get away from anxious thoughts.

How do you know when it’s time to seek professional help?

Living through a global health crisis is a new and trying experience for most, and some who have never experienced serious mental health issues may wonder if, and when, they need to seek help.

Gold assured that “it’s okay to always ask for help,” and that no one is going to turn you away for not having enough symptoms.

She also suggests that everyone becomes familiar with the common signs of mental distress:

Sleeping too much, or too little

Eating too much, or too little

Not interacting as much with friends or family

A lack of joy in things you used to like

Low energy

While these aren’t always definite signs, they are indicative of an affected headspace, which may require help from a therapist.

How do we deal with loneliness?

For many people living alone, social distancing has cut off everyday interactions that are critical for mental stability. Gold said she understands this on a personal level since she also lives alone.

“This is the first time it’s been very evident that I live alone,” she said.

Gold recommended everyone should make an effort to reach out to friends or family to maintain social interactions. That could involve just talking, or setting up a game or movie viewing night.

“It actually feels more like work … but it’s worth doing in the end,” she said.

She also suggested that, in this moment of isolation, that we can find the things we truly enjoy doing by ourselves.

PBS NewsHour viewers also weighed in with ways they have been coping and finding joy in things they enjoy, such as bike rides, working out, learning to meditate, knitting and watching new or favorite TV shows.

“Find what coping skills work for you,” she said.

What are some resources available during COVID-19?

As the pandemic continues, many doctors are concerned about the wave of mental health issues caused by extensive social isolation and anxiety about the virus. Gold said it’s important to first break down the distinction between mental and physical health.

“I think we like to separate things, but I don’t know if that necessarily helps us,” she said.

Many physical issues, like a lack of protective gear and helping to treat those with COVID-19, directly affect a person’s mental health. Gold said that means we’re probably already seeing the effects of poor mental health on a portion of the population.

Gold listed a few helpful mental health resources that are available during this pandemic.

To find a therapist, Gold recommended Psychologytoday.com.

For members of the Trans community, Gold recommended calling or texting the Trans Lifeline.

For the emergencies, Gold recommended the Crisis Lifeline, or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

For frontline workers in particular, she recommended Project Parachute or Emotional PPE.

Gold said online services like Teladoc are helpful, but are limiting in many ways, even for the therapist.

“It’s really hard for me, I think I’m really used to the human experience,” she said. “But it’s a lot better than nothing,” particularly during this pandemic, where social distancing has been key to curbing the spread of the virus.

While telemedicine can be cost effective for some, Gold said many people do not have easy access to either the internet or a device in order to use these services.

“This is not something we can just assume people can use,” she said.

View the whole interview here: https://youtu.be/iS7z1XX-e5Y

The wise words of Olaf

This can be a great time for self-reflection

What is your anxiety telling you?

Yoga for better sleep

With Senior Year In Disarray, Teens And Young Adults Feel Lost. Here's How To Help

For many young people, sheltering at home means missing milestones and public recognition of their achievements. This is especially true for seniors graduating from high school and college.

Kendall Smith, a high school senior who lives in Tallahassee, Fla., says her school has many traditions leading up to graduation. But this year things are very different.

One of the most eagerly anticipated events is Grad Bash, a rite of passage when all graduating seniors head off to the Universal Studios theme park in Orlando. "It's something we've looked forward to since we were freshmen," Smith says. "And I remember hearing about all the memories and seeing them on Snapchat and Instagram, and being so excited about going with my friends."

So it was understandably disappointing when this highly anticipated event was canceled.

Smith, who plays flag football, says a big celebration for senior athletes was also canceled. "It's this huge event where people walk through the middle of the field with their parents and their family and they have flowers and you just really feel special that night," she says.

Teens are suffering from missing out on these experiences and the opportunity for connecting with their peers at critical transitions into adulthood, says Dr. Ludmila De faria, a psychiatrist with Florida State University.

She says they're "mourning the loss of important developmental milestones they were supposed to be doing at this time in their lives."

And experts advise parents to take these issues seriously and try to help kids process them.

These losses are also experienced by college students.

Waverly Hart is 21 and a senior at the College of Wooster in Ohio. One of the most memorable graduation events is I.S. Monday, short for Independent Study Monday, when seniors celebrate finishing their theses. Hart says it typically occurs on the first Monday after spring break.

"All the seniors skip classes, and there's a huge parade. And everybody on campus cheers us on and that's something that we've been looking forward to since we were admitted to Wooster. And now we won't get to experience that ... ever," Hart says.

As a competitive cross-country runner, Hart was looking forward to taking part in the last season of her college career, but that was canceled as well. "And it's really heartbreaking to know that the last race I competed in was indeed my last race ever. And I won't get another chance to compete in the black and gold Wooster uniform."

Graduation itself has been "postponed," she says, although she expects it will be officially canceled sometime soon.

As a freshman at the University of Michigan, 19-year-old Sophie Busch never expected to end up home before finishing her first year. She's proud of her freshman research project on childhood obesity and is disappointed she won't be presenting her findings at a large research symposium at the end of April. (It was canceled.)

"I was looking forward to presenting my research with the other freshmen in my lab, and I was just excited to show it to my other friends — and my parents and grandma were also going to come."

De faria, who works with student mental health, says when young people miss kinds of momentous events, "it's almost like they are forced to regress a little bit, or at least not progress as expected on their developmental milestone."

And she says, college students in particular are losing their support group during an important developmental phase. They had moved away from their families of origin, which is part of a process called individuating.

"They're finding their people, their identities and developing their ability to take care of themselves," she says. "The people they live with, their roommates in college become their primary source of support. They lost that suddenly."

This can be traumatic for a generation that "already suffers high levels of anxiety," she says. It puts them at greater risk of developing clinical anxiety and depression. Students like this may require some sort of therapeutic help from home, she says.

Many parents may be at a loss for how to reassure their children during a time of such great uncertainty, which could make things even harder on teens and young adults.

"It's unprecedented for all of us, but it's completely new for teens and young adults — and they don't have the wealth of experiences that older individuals have with transitions," says psychologist Lynn Bufka, spokesperson for the American Psychological Association. "They're trying to figure out how to do transitions and manage change within an environment where everything seems upside-down for them."

Bufka says she's hearing from young people that the situation is "very new and very different and very hard for them," she says.

"That need for strong peer relationships, coupled with less experience dealing with and adapting to adversity, means you have a generation that is going to struggle more," she says.

But there are ways to help them cope. Here are a few things parents can try.

Acknowledge their feelings

Bufka says an important way for parents to help high school and college students by simply acknowledging their feelings — the sadness and disappointment they feel about the loss of prom, celebrations and graduation.

Parents should recognize that for many young people, "this is the biggest thing they've experienced in their lives," she says. "They're too young to remember 9/11. Collectively as a generation, this is a really big experience for them."

When you're young, understanding that life is just not as predictable as they might have thought can be scary, she says. Parents can help by letting them talk about it.

Encourage them to stay connected

Young people need to establish a cushion of social connection they can lean on through these times.

Bufka says staying socially connected, even virtually, can be helpful. In fact, she prefers to describe distance precautions as physical distancing, not social distancing. "It's important to maintain social connection and intimacy even if this is not in person," she says.

And she encourages young people to take advantage of the many ways to socially connect, with all kinds of shared online activities, including group chats, dinners, TV and even movie watching.

Shift focus to what they can control

Bufka recommends talking to your teen or college-aged child about the things they do have some control over

Graduation may be postponed or canceled, but young people can plan special events for after the pandemic has ended. Perhaps a trip with best friends or a post-graduation party. Focus on the positive events that can occur at the end of this crisis. Envision how you can celebrate, and maybe even start making plans now.

Emphasize the greater good

It can help to point out to young people that they are making sacrifices right now not just for their own health and safety, but for the greater good. She points to a study that looked at previous infectious disease crises, including the 2003 SARS and the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. People are able to cope better, she says, when they "think about the altruistic reason they're doing this."

Changes in everyday life to limit the spread of disease may be hard, but "we're in it together and we're in it to benefit the larger community and to have a good impact on overall health and wellbeing."

Florida high schooler Smith says she and her peers understand this well.

"As disappointed as we all are that we're missing out on these important milestones in our life, we do understand that this virus is killing people and that if we don't sacrifice these things that we might contribute to the problem."

She adds they wouldn't want to be "the reason that a student takes home that virus to their family, maybe a grandparent that can't fight that off, or maybe somebody with asthma that doesn't have the lungs to be able to deal with coronavirus."

"We understand these sacrifices need to be made, and we know that we are doing our part in this, doing what we can for society," she says.

In the end, Bufka says once young people get through this crisis, they will realize they can handle tough situations and get to the other side.

"It will make us stronger — sometimes we surprise ourselves."

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Ways to reframe irrational thinking

When a Child's Emotions Spike, How Can a Parent Find Their Best Self?

With families around the world spending unprecedented amounts of time in close quarters – and under varying degrees of stress – emotions can run high.

In good times and in hard times, parents can take steps to help their children strengthen their emotional competence. As parents, “we are co-creating the emotion system for our kids” says Dr. Marc Brackett, Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and author of "Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help Our Kids, Ourselves, and Our Society Thrive."

“Emotions are constructed by our interactions with other people,” says Brackett. Caring for a child's emotional development is key to life-long flourishing “because while part of our success in life is knowing how to count and read and write, a bigger part of our success in life is knowing how to get along well with other people and deal with life's ups and downs.”

Parents may not always feel up to this task – especially in challenging moments – and yet parenting can be an opportunity for adults to strengthen their own emotional intelligence. In order to help children regulate their own emotions, we must keep working on regulating our own, says Brackett. “It's all about adult development.”

Responding to Children’s Signals

The emotion system is a signal system, and how we feel on the inside drives how we approach a task, says Brackett. How we read and interpret the emotions in other people also sends signals to our brain. “When I look at your facial expression, if you are displaying a lot of anger, it says to me, ‘Avoid. Avoid. Avoid!’ That's what emotions do. They signal,” says Brackett.

But here’s a crucial difference when it comes to parenting: when our children send out classic “avoid” signals – such as yelling or angry expressions – this is actually a signal to approachthem. “That’s really critical for parents: for kids, all emotions are approach.”

As adults, we often give our friends and partners space when they are in a bad mood. But with young kids, “you always have to follow up,” says Brackett. “It’s your moral obligation to know what your child is feeling and to support them in developing healthy strategies.”

This can be very difficult. When adults are under stress, our instinctive biological response is to fight, flee or freeze. “Many parents get easily activated and triggered by their kids. The kid throws something, the kid is crying, the kid is screaming, ‘I hate you!’ and all of a sudden you're triggered.” In these moments, take a deep breath and try to replace “fight or flight” with “stay and help,” says Brackett.

When both parent and child are emotionally activated, it’s “very hard to problem solve” – so parents may need to take a walk or time to collect themselves. But it is critical to circle back and attend to the child.

Getting Curious About Emotion

Feelings offer information about what might be happening within the individual. One strategy for improving emotional regulation is to become an “emotion scientist.” Brackett encourages adults to “get curious” about emotions – their own and their children’s. Parents are often tempted to be an “emotions judge” by challenging, shaming or minimizing a child's big feelings.

In contrast, “the emotion scientist is the curious explorer of their child’s emotions,” says Brackett. A preschooler’s angry outburst might indicate they are overstimulated, stressed, in need of connection, hurt by someone’s actions, or in need of a snack or a nap. “The emotion scientist says, ‘My child needs some support here.’ Let me see what kind of strategies I can use to help my child deal with emotions. The emotion judge says, ‘Get over it.’” When adults train themselves to see all emotions as information, they can use that data to support their child.

Using open-ended questions can help children process emotions. Rather than saying, “Pull it together,” a parent might say, “It looks like you are really upset about something. What happened? Tell me more about that.”

Brackett recommends the phrase, "Tell me more" because it’s simple, gentle and indicates non-judgemental curiosity.

The Skills of an Emotion Scientist

Brackett and his team use the acronym RULER to describe five key skills parents and teachers can help children cultivate. Here is how he describes them in his book:

R: RECOGNIZE our own emotions and those of others, not just in the things we think, feel, and say but in facial expressions, body language, vocal tones, and other nonverbal signals.

U: UNDERSTAND those feelings and determine their source— what experiences actually caused them— and then see how they’ve influenced our behaviors.

L: LABEL emotions with a nuanced vocabulary.

E: EXPRESS our feelings in accordance with cultural norms and social contexts in a way that tries to inform and invites empathy from the listener.

R: REGULATE emotions, rather than letting them regulate us, by finding practical strategies for dealing with what we and others feel.

For young children, developing an emotional vocabulary is a powerful tool. “Labeling emotions is a form of communication. It helps us make meaning of our experiences and communicate that to others.” Learning the difference between anger, frustration, annoyance, and disappointment can help children think about the causes of their emotions.

Take disappointment and anger, says Brackett. “Oftentimes they look the same, but their underlying cause is completely different. One is about unmet expectations. The other is about injustice. And I would say 99% of the people I talk to have no clue about that. Yet the strategy for helping my child manage disappointment would be very different than it is for anger.”

Take a child who says, “I hate school.” When the adult gets curious and asks questions, the child offers, “Nobody wants to play with me.” Now you are learning something, says Brackett. Ask a few more questions and you might discover that they sit by themselves as recess. “And now you realize that your child is feeling left out. They are not just sad – they are actually feeling isolated and alienated. That points to a different strategy you might take as a parent.”

“How Would My Best Self Respond?”

Children are great anthropologists of parent behavior. They watch how we handle stress and how we recover from episodes of fear, frustration, anger, and disappointment. Brackett urges parents to pay attention to their self-talk – because our children are listening when we say “I’m an idiot” or “ I’m going to lose it.”

With practice, parents can use self-talk to model healthier ways of moving through emotion. It might sound like, “Mommy had a really long day at work and needs a little space to take a deep breath. I want to talk to you, but first I need to take a little break and then come back to you”; or instead of saying “I’m so stupid! I always mess up this recipe,” saying “Well, daddy did it again! So now I’m going to take a step back and figure out what went wrong and how to fix it.”

When parents feel their emotions spike, they can take a meta moment, says Bracket. This is a process that helps us build awareness of our triggers, “and parents have a zillion of these – when my kids pull my hair, when they're nagging, when they are whining about going to bed, when they refuse to eat things.”

First, just be aware of your triggers. Next, notice where your brain goes when you experience one. What is your automatic, go-to self-talk? Is it “I hate my life?” Is it “I can’t handle this?” What is your go-to behavior?

When you are aware of your triggers and your habitual, unhelpful reactions, you can begin to purposefully move away from these into healthier ways of responding. “Immediately pause and take a breath,” says Brackett. “You have to give yourself space. That deep breath helps you deactivate the reaction and activate your best self. Ask yourself, ‘How would my best self respond?’”

Keeping your “best self” in mind helps you make better decisions in the face of strong, uncomfortable emotions. As Brackett shared, his “best self” is kind and compassionate. So when he’s triggered, he asks himself, “How does a kind, compassionate dad respond?”

These meta-moments “help you take a step back, shift your attention away from the stimulus, bring it back to your values and goals as a parent. And by the way, it's really freaking hard! So give yourself permission to feel, fail and forgive.”

The Good News For Parents and Kids

All parents have moments when they overreact – especially when they are under stress. “The good news is that we are more resilient than we think we are,” says Brackett. “We can undo things and learn new things. And that means you can start today and start tomorrow. We can change the relationships we have with our kids if we work on developing ourselves.”

In addition, “research shows that the mere presence of a caring and loving adult is a co-regulation strategy. If our children believe in their soul that the person they are with cares about them and is there for them – even if that person doesn’t say anything – that’s a strategy. Think about those people who, just being in their presence, make you feel safe.”

It’s never too late to strengthen your emotional skills and help your children strengthen theirs. “A child’s brain is still plastic, so the minute you start regulating your emotions better, their brains will change to reflect that.”